Sources Jean Monnet Foundation for Europe, Lausanne – Jean Monnet Institute, Houjarray

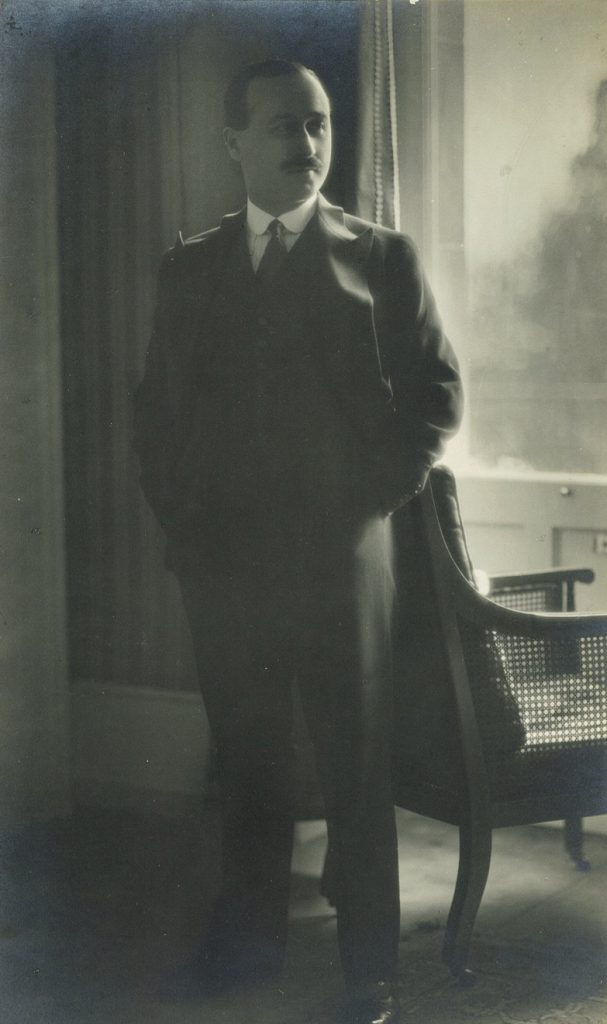

Jean Monnet was born in Cognac on November 9, 1888 into a family of cognac merchants. The flourishing business of the JG Monnet & Cie family company exposed the young Jean very early to the bredth and diversity of the world At the family table, customers and agents come from all horizons and speak all languages.

At sixteen, Jean Monnet leaves for “the City” of London to learn English and business from his father’s agent. At the age of eighteen, he embarks for America and discovers with fascination its immensity, its dynamism, and the entrepreneurial spirit of the pioneers. He also discovered his own great talent as a negotiator.

Reformed for health reasons, Jean Monnet does not go to the front when the war breaks out. Having noted the total absence of coordination between the French and the English, particularly on the maritime level, he manages to meet René Viviani, the French head of government, to submit his ideas to him. Viviani is convinced and at age 26, Monnet devotes himself successfully to setting up Franco-British supply committees.

Drawing on the experience and reputation he acquired during the war, Jean Monnet contributes to the creation of the League of Nations and becoms its Deputy Secretary General. It contributes to the settlement of numerous international crises but also notes the limits of coordination between States and the immobility engendered by the exercise of the veto.

After a stint in Cognac in order to rebuild the family business in the grip of difficulties, Jean Monnet joins an American private bank and participates in particular in financing operations for Poland and Romania. He leaves for the United States in 1929, earns and then loses a lot of money during the stock market crash.

Jean Monnet meet sin August 1929 a young Italian girl nineteen years his junior. He marries Silvia de Bondini in Moscow in 1934. From this union of 45 years will be born two daughters, Anna and Marianne.

Jean Monnet is called in 1934 by TV Soong, Chinese Minister of Finance, to set up a consortium intended to finance Chinese infrastructure, the CFDC. He facilitates the creation of the CFDC to which he rallies the largest local banks in order to attract foreign capital. The CFDC obtains many credits, in particular for the financing of railways. Its progress is only halted by the war in 1939.

The clouds of war are gathering over Europe. The French head of government Edouard Daladier instructs Jean Monnet, who has many contacts in the Roosevelt administration, to negotiate the purchase of American planes in an attempt to fill the air deficit with Germany. Monnet manages to buy 400 planes which unfortunately arrive too late to prevent defeat.

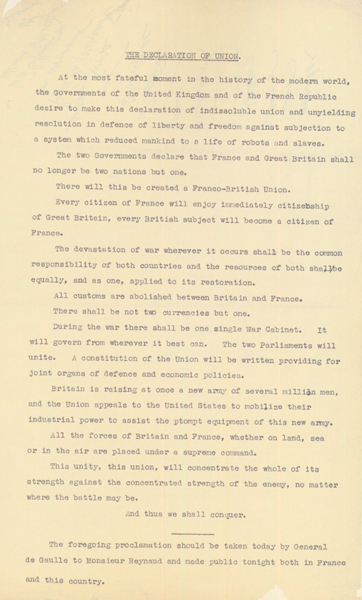

In June 1940, Jean Monnet convinces Churchill, his cabinet, and de Gaulle, of the interest of an immediate and total fusion of France and the United Kingdom. On Sunday June 16, general de Gaulle himself dictates the terms of the agreement to Paul Reynaud, President of the Council. The same day, Paul Reynaud is replaced by Philippe Pétain who proposes an armistice to Hitler.

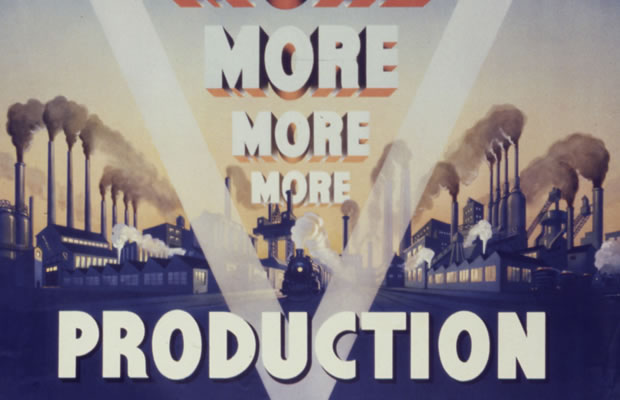

Jean Monnet offers his services to Winston Churchill, who asks him to return to Washington to resume his task of sourcing supplies on behalf of the British government. Jean Monnet becomes one of the major architects of the Victory Program which turns the US into “the arsenal of democracies”.

While the forces of Free France are getting organized in Algiers, Jean Monnet is sent there by President Roosevelt to ensure that the conditions for supporting the new French command are met. Initially suspicious of de Gaulle, Jean Monnet supports him at the head of the CFLN and then of the provisional government

It’s time to rebuild. Jean Monnet is appointed Commissioner General for Planning by general de Gaulle. He imagines a flexible planning method involving all the players in the economy. The approach is a success and will be called “French-style flexible planning”.

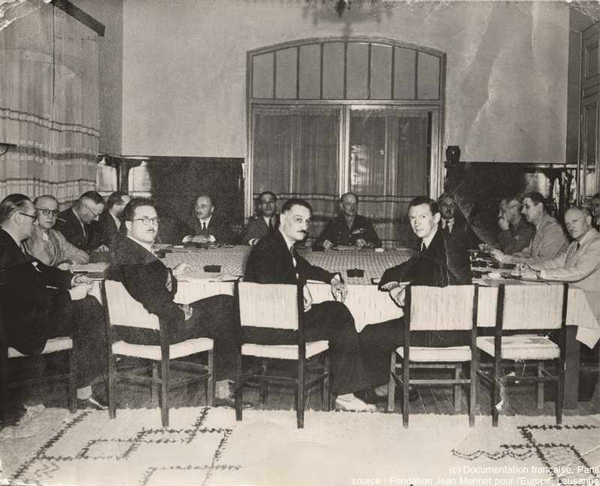

Convinced of the need to unite the peoples of Europe and in particular to associate Germany and France with this new Europe, Jean Monnet proposes to Robert Schuman the pooling of the coal and steel resources of the two enemies of yesterday, under the authority of an independent entity. This is the ECSC, the first step of the European Community with which six countries are associated. Monnet becomes its first President.

Following on from the ECSC, Jean Monnet proposes to René Pleven, French head of government, a plan to create a European army, the EDC. This would make it possible to associate Germany with a European defense without seeing the rebirth of a German army. The EDC is approved by four of the six Community countries, including Germany, but is rejected by the French Parliament. Jean Monnet resigns from the High Authority of the ECSC.

Jean Monnet creates the Action Committee for the United States of Europe to devote himself entirely to European unification. The vast majority of progressive parties and trade unions representing the six member countries are represented. Euratom, the Common Market, political Europe and monetary union are its priority objectives.

Monnet and de Gaulle will regularly disagree over Europe. De Gaulle wants a “Europe of nations” and is wary of American influence on European construction. Monnet is convinced of the superiority of the Community method, conceived as “a permanent dialogue between a European body responsible for proposing solutions to common problems and the national governments which express national points of view”.

Jean Monnet and his action committee ardently wish for the United Kingdom’s accession to the Community. Twice, General de Gaulle opposes it. The coming to power of Georges Pompidou in France and of Willy Brandt in Germany relaunch the accession process. The United Kingdom joined the common market in 1972 and confirmed its membership by referendum in 1975.

Jean Monnet wishes to structure relations between Europe and the United States in a partnership of equals. He expects a lot from the young President Kennedy. His assassination affects him and puts an end to these hopes.

The beginning of the 1970s was conducive to a revival of the economic and political union of Europe. The principle of a monetary union and a European monetary fund, supported by the Monnet committee, is progressing. He approves of the formalization of the European Council of Heads of State desired by Giscard d’Estaing and the principle of the election of the European Parliament by universal suffrage.

Jean Monnet puts an end to the activity of the action committee and retires to his house in Houjarray in the Yvelines in 1975 at the age of 87 to write his Memoirs. He receives the title of Honorary Citizen of Europe and dies on March 16, 1979. His ashes are transferred to the Panthéon in 1988.

Jean Monnet was born on November 9, 1888 in Cognac in Charente into a family of cognac merchants. His father Jean-Gabriel, son of winegrowers, had risen to the coveted rank of merchant and had taken the helm in 1897 of a cooperative of small producers which he had gradually bought to form a family company, JG Monnet Cie.

The Charente has been open to the outside world since the 12th century, very early exporting salt and then wine to the British Isles. Since the 19th century, its eaux-de-vie have been appreciated throughout the world and it is significant that the main producers of the time, Hennessy and Martell, were both of British origin. The Cognac region was therefore very early aware of the vastness of the world. People were naturally more interested in international affairs, on which commerce depended, than in what might happen in France.

It is in this context that the young Jean Monnet grows up. He sees clients and associates from all horizons at the family table, speaking all languages and reporting news from around the world. The teenager is fascinated by their stories especially since, although a good student, he has little taste for theoretical learning of things.

In 1905, at just sixteen years old, Jean Monnet leaves for “the City” of London where he learns English and business from his father’s local agent. At eighteen, the young man feels ready to face America and embarks on the first of these great transatlantic crossings that he would love all his life. His father advises him: “Don’t take any books. No one can think for you. Look through the window. Talk to people”.

America is a revelation for the young Jean: the infinite spaces, the simplicity of the contacts, the entrepreneurial spirit fascinate him. There he weaves bonds of friendship and trust early on and discovers his great negotiating skills. At the age of 22, the young Monnet signs an important exclusive distribution contract for western Canada with the powerful Hudson Bay Company for family cognacs. On this occasion, he establishes strong personal ties with the directors of this company, which has substantial financial resources and a large fleet of merchant ships at its disposal.

It was in July 1914 at Poitiers station, returning from Canada, that Jean Monnet learns of the general mobilization. Reformed in 1908 for lung problems, he cannot be mobilized, but he intends to contribute as he could to the war effort. Drawing on his experience as a charterer and his knowledge of England, the young merchant notices the disorderly and uncoordinated use of the French and English merchant fleets, a catastrophic waste in these times of war. He is convinced of being able to propose solutions and to take advantage of his relations with the Hudson Bay Company. His father, to whom he confides his findings and his intention to meet the head of the French government René Viviani to explain his views, tries to reason with him: “Even if you were absolutely right, it’s not at your age, nor in Cognac, that you will change what our great chiefs decide in Paris”.

What followed proved him wrong because after having obtained an audience in the midst of the Battle of the Marne with René Viviani, withdrawn to Bordeaux, the young Monnet finds himself propelled to London to implement his ideas and the Hudson Bay Company signs an important contract for maritime and financial assistance with the French government. Jean Monnet then devotes himself to the establishment, from London, of Franco-English supply committees, an action about which the great historian Jean-Baptiste Duroselle did not hesitate to write in The great war of the French In a sense, one can say that Foch’s flamboyant victory was facilitated and even made possible by the obscure action of Jean Monnet.

At the end of the war, Jean Monnet tries, in vain, to preserve the economic organization of war to organize the transition between war and peace. He regrets seeing the Allied committees dismantled because he is convinced that the Franco-British coordination structures that are so useful in times of war can also be so at the time of reconstruction. Having acquired in a few years a solid reputation as an organizer and a great influence, Monnet is entrusted with new functions related to the problem of supplying defeated Germany and the administration of the occupied Rhineland.

From 1919, Jean Monnet contributes to the creation of the League of Nations, wanted by American President Woodrow Wilson, the first international organization devoted to the maintenance of peace. When it was created in 1920, the young man, then aged thirty-one, was appointed Deputy Secretary General of the organization. He is the number two in charge of its operational functioning, its real linchpin. Monnet particularly endeavors to settle the conflict between Germany and Poland relating to the delimitation of the coal basins of Silesia and the Saar and works for the economic rescue of Austria.

However, the Deputy Secretary General is disappointed with the functioning of the organization he leads. He regrets that governments and their representatives seek more to defend their own interests than to resolve the common problems with which they are confronted. The right of veto is for him the symbol and the cause of the powerlessness to overcome national selfishness.

It was without bitterness that Jean Monnet resignd from the League of Nations in December 1922 to join Cognac and help his father rebuild the family business damaged by American prohibition. His younger sister Marie-Louise having convinced him that his return was essential, the former leader of the League of Nations actually finds a difficult situation in Cognac. His father Jean-Gabriel is reluctant to get rid of his old cognacs which no longer have the favor of a public looking for younger and less expensive eaux-de-vie. In a few months, helped by the resumption of classes, Monnet puts the family business back on its feet, notably by sacrificing his father’s old stock of cognac in favor of younger eaux-de-vie.

Very quickly, the Cognac business is no longer sufficient for him, and when he is approached in 1926 by an American investment bank, Blair & Co, to set up an office in Paris, Monnet does not hesitate for long. American banks, in full expansion, wanted to take advantage of the period of reconstruction in Europe to finance large industrial and national loans. Jean Monnet has the perfect profile. He has participated in programs to rescue national economies and currencies within the framework of the League of Nations, in particular in Austria, understands the functioning of the administrations, and he benefits from a solid network and reputation. It is therefore within the framework of the Blair & Co bank that the young banker (he is not yet forty years old) is led to play a decisive role in the rescue of the Zloty of Poland and the Leu of Romania.

In 1929, before the October crash, Jean Monnet leaves for the United States to take the vice-presidency of an American bank resulting from the merger of his bank and a large local bank, Transamerica. In the space of a few months, he wins and then loses a lot of money. He is credited with this saying about this period: “I earned a lot of money without pleasure and I lost it without regret”. He retains from the crisis of 1929, the risks of which had been visible for a long time, that “Men accept change only in necessity and only see necessity in crisis”. Jean Monnet continues his activities as a banker in the United States until 1934, founds a business firm, Murnane & Co, then leaves for Shanghai.

He goes to China at the request of TV Soong, Minister of Finance, to set up a reconstruction plan capable of attracting Chinese and foreign capital. But when Jean Monnet leaves for Shanghai, his life has dramatically changed. He is about to marry Silvia de Bondini, a young Italian nineteen years his junior, whom he met in Paris in 1929.

In August 1929, a few months before the Great Depression, Jean Monnet hade made the encounter that would change his life. During a dinner at his home in Paris attended by René Pleven, he had met Silvia, the young wife of an Italian businessman. The case is complicated because Silvia is married under Italian law and her husband refuses her a divorce. The solution proposed by his friend Ludwig Rajchman, former director of the League’s hygiene section, is audacious: young Silvia has to go to Moscow, take Soviet nationality and, taking advantage of a Russian law, divorce unilaterally to marry Jean Monnet. This is how the case goes. Monnet arrives in Moscow from Shanghai by Trans-Siberian in April 1934 to marry Silvia. Jean Monnet described this episode in his Memoirs as “the best deal of his life”. Indeed, the union of Jean and Silvia Monnet lasted 45 years, until his death in 1979 and was an essential source of happiness, stability and serenity. Together they had two daughters: Anna born in 1931 and Marianne born in Washington DC in 1941.

Jean Monnet’s mission to China could have taken place under the aegis of the League of Nations, but Japan opposes it and Jean Monnet leaves for Shanghai on a private basis under the name Monnet-Murnane & Co., a company created for the occasion with George Murnane, an American friend. In this private setting, Monnet nevertheless continues to collaborate closely with former members of the League of Nations such as his friends Arthur Salter and Ludwig Rajchman. In China, the fundamental question is the same as that with which Monnet has been confronted in other financial recovery or reconstruction enterprises: how to create locally the conditions for issuing international loans capable of attracting the necessary foreign capital to the reconstruction of Chinese industry and infrastructure? To do this, he facilitates the creation of the China Finance Development Corporation (CFDC) to which he rallies the largest Chinese banks. The objective is to attract foreign capital in the form of credits and to allocate them to the Chinese private and public sectors. It is a success, the CFDC develops and obtains many supports, in particular for the financing of the railways. Its progress is only halted by the war in 1939.

The experience is rich for Jean Monnet, China is a new horizon. There he rubs shoulders with the most influential personalities of the country: TVSoong, Minister of Finance, his three sisters, two of whom are married to Sun Yat Sen (founder of the Chinese nationalist party) and to Tchang Kai-chek. Chiang Kai-chek himself then exercised his power over China and nothing was done without his support. Jean Monnet gradually establishes a relationship of trust with the Chinese leader who confides to him one day “that he would make a good general if he weren’t so weak with his friends” and – ultimate compliment – that there is “something Chinese in him”. Monnet developed during this stay in Shanghai a great admiration for China and for the Chinese, of whom he wrote in his Memoirs that they seemed to him “much more intelligent and subtle than Westerners”. However, he also admitted that he never really understood them.

On his return from China in 1936, Jean Monnet settles with his family in the United States. Since 1933, he knows the Roosevelt administration well within which he has many friends. Monnet had been convinced for several years of the threat posed by Hitler and from 1938 he is worried like others about the manifest inferiority of the French air force. It is clear that only substantial American aid will enable France to make up for this inferiority. Monnet’s unique profile naturally designates him to play the role of intermediary between the French government and the Roosevelt administration. On the advice of Ambassador William Bullitt, he is instructed by Edouard Daladier, head of the French government, to negotiate the purchase of American planes. Jean Monnet meets President Franklin Delano Roosevelt for the first time on this occasion. He is introduced to him by Bullitt as “the man qualified to handle this aircraft question, a long-time intimate friend whom I trust as a brother”. Monnet must convince the Americans to circumvent the Neutrality Act which constrains them and find in France the means to finance these purchases. Roosevelt obtains the lifting of the Act and a bold solution is identified for the financing of the planes: to requisition the undeclared gold held by the French in the United States.

Jean Monnet will manage to order more than 400 planes after the Munich agreements, which will open the way to other orders, but until the declaration of war France will unfortunately not be able to obtain planes in sufficient quantity. The fact remains that Jean Monnet has now returned fully to war and public action, which he will never leave. Continuing the role he played during the First World War, Monnet chairs the Franco-English supply committee from December 1939. Alas, time runs out and when Hitler launches his offensive on May 10, 1940, France still lacks planes.

In June 1940, Jean Monnet refuses defeat. He, who has had the reflex of collective action since the First World War, takes up a proposal as audacious as it is desperate. By a note entitled “Anglo French Unity”, he convinces Churchill, his cabinet, and de Gaulle, cornered by the debacle, of the interest of an immediate and total fusion of France and the United Kingdom. A single Parliament and a single army to face Germany together. On Sunday June 16, General de Gaulle on a mission to London himself dictates the text of the note to Paul Reynaud, head of government, over the telephone. But the project is quickly buried because the same day, Paul Reynaud is replaced by Philippe Pétain who proposes the armistice to Hitler.

In his Memoirs, Jean Monnet notes about this episode: “If it was without romanticism that I envisaged the fusion of two countries and the common citizenship of their people (…) these days of 1940 had a strong effect on my conception of international action”. He had again experienced, in an even more cruel way than in the League, the limits of coordination alone when total unity is necessary. In terms of method, Monnet had once again demonstrated his ability to grasp a radical idea – even if it had already been formulated by others – to formalize it and to set about convincing at the precise moment when he knows that the minds will be ready to accept it.

The next day, the evening of June 17, Jean Monnet receives General de Gaulle at his London home, who is preparing his June 18 appeal. The two men both refuse defeat but they have a different appreciation of the situation and everything opposes them in terms of personality. General de Gaulle sees his own destiny in that of France while Jean Monnet seeks a global solution to the conflict, which he knows will include the allies.

The armistice of June 1940 rendered obsolete the Franco-English Supply Committee headed by Jean Monnet. He then offers his services to Winston Churchill. The British Prime Minister asks him to return to Washington to resume his sourcing task, this time on behalf of his government which continues the fight against Nazi Germany.

In August 1940, Jean Monnet arrives in Washington. He finds there an isolationist America which obviously does not have the industrial apparatus necessary for the production of weapons in sufficient quantities to ensure the victory of the Allies. The production of planes in particular is not at the level required to compensate for the superiority of the Luftwaffe. The question of the financing of supplies also arises again.

Jean Monnet, his team and his friends from the Roosevelt administration set out to precisely assess equipment needs and compare them to American production capacities to clearly show the deficit to be filled. For this, they use a tool that Monnet will use many times in his career: the famous “Balance Sheet”. The conclusion is clear: the American production programs are insufficient, and they must be at least doubled. Jean Monnet, far from being a technician himself, turns into the strongest advocate of total production, constantly repeating that it is better to have ten thousand tanks too many than one too few. He thus convinces the American administration to double their production program, turning the United States, in the words of President Rooselvelt, into “the arsenal of democracies”. Monnet also plays an essential role in setting up the “Combined Production and Resources Board”, a system for optimizing the allocation of equipment between Americans and British on the same principles as those which had been set up in the Franco-British councils of 1916 and 1939.

Jean Monnet’s role in the success of the Victory Program was decisive. The English economist John M. Keynes will say of Monnet that his action in Washington in 1941 probably shortened the war by one year. Felix Frankfurter, then a Supreme Court judge, described Monnet as a “creative and energizing force in the development of our defense program” and another senior American official in office in 1941 judged that “Jean Monnet was a teacher to our Department of Defense “.

The landing of the allies in North Africa in November 1942 marks the beginning of the liberation phase. Jean Monnet is convinced that American aid will be essential for the reconstruction of France and Europe and that the United States must be reassured about the legitimate and democratic nature of the entity which will be called upon to assume power in France at the time of liberation. In this respect, neither Admiral Darlan, who had recently joined in Algiers, nor General de Gaulle, still based in London, are fully suitable for Jean Monnet and President Roosevelt.

General Giraud initially seems a good compromise; he commands the French forces in North Africa and is favored by the American administration. By contrast, Amercians distrust General de Gaulle and fear what they see as his authoritarian tendencies. After the assassination of Darlan, General Giraud takes the head of the “civilian and military chief command”. It is at this time that Jean Monnet arrives in Algiers, mandated by President Roosevelt with Churchill’s agreement, to ensure that the conditions for American support for the new French command are met. In particular, the question of the continuous references to the government of Pétain and the maintenance of certain anti-Semitic laws, unacceptable for Jean Monnet, must be settled as a matter of priority. Monnet has the advantage in the eyes of the Americans and the British of being a neutral civilian aspiring to no power for himself and, in the words of Roosevelt, “a man best representing France and French spirit in North America”.

Initially well-disposed towards General Giraud, Monnet quickly judgeds him with severity: he turns out to be a poor politician and his ideas are considered reactionary. When de Gaulle finally goes to Algiers, the French Committee of National Liberation (CFLN) is established, co-chaired by the two generals. Jean Monnet becomes a member, in charge of refueling and rearming. There, he gradually realizes the obvious: despite his reservations about the individual, only General de Gaulle is up to the task which requires stature and great political sense. From then on, Jean Monnet sets about facilitating the process of stabilizing the Committee for the benefit of de Gaulle, whose eminently personalized conception of power he nevertheless continues to regret. Of this episode in Algiers, Monnet would write in his Memoirs “I have had the experience a hundred times in my life that questions of people were major obstacles to common organisation and to the progress of action”.

At that time already, the differences of view on Europe become clear between Jean Monnet and General de Gaulle. In 1944, Jean Monnet returns to Washington to obtain lend-lease aid, the aid that France would need for its reconstruction and to seek recognition of the provisional government of General de Gaulle by the Roosevelt administration. It is also his objective to clearly express to the Americans – in the name of the provisional government – the refusal of the French to see them exercise any supervision over France at the liberation. Monnet in particular opposed American plans to print the banknotes which would be put into circulation in France at the liberation. Joining Monnet in Washington are Frenchmen on whom he will rely heavily later, such as René Mayer, Hervé Alphand, and Robert Marjolin. Together, they work, not without difficulty, for the recognition by the United States of the provisional government and negotiate, then supervise, supply agreements of a fabulous value for the time of 2.5 billion dollars. On May 8, 1945, Germany is defeated and the time for reconstruction begins. The provisional government, led by de Gaulle, takes the reins of the country.

It was in Algiers that Jean Monnet expressed for the first time his convictions – largely matured in Washington in 1942 within the European community there – on the way in which European nations must rebuild themselves to ensure their future prosperity and prevent the tragedies of the past from reoccurring: “There will be no peace in Europe if the States rebuild themselves on the basis of national sovereignty”, he writes in a foundational note dated August 5, 1943. In this note, he also expresses his conviction that “the countries of Europe are too small to ensure prosperity for their peoples (…) and that they need larger markets (…)”. And to conclude: “On the solution of the European problem depends the life of France”.

After the war, it is time to rebuild. Jean Monnet recommends to General de Gaulle to put in place an ambitious plan for the reconstruction and modernisation of the French economy. : “You speak of greatness, he said to him, but today France is very small”. Despite their past differences, General de Gaulle has confidence in Monnet’s organizational talents and ability to unite. He thus appoints him General Commissioner of the Plan. Jean Monnet settles in his Houjarray house in the Yvelines near Paris where he lived until his death in 1979.

The vision that Monnet and his small team develop consists in relying on unquestionable quantitative analyses, identifying the few key sectors on which to concentrate, and organizing the joint work of the social partners and plan technicians. This is the birth of what will be called “French-style flexible planning”. The rigor of the method and the clarity of the plans will contribute to the allocation of Marshall aid to post-war France.

In January 1947, after a long series of consultations, often confidential, with nearly a thousand actors in the economy (employers, trade unionists and civil servants), a plan was presented to the government of Léon Blum. The strength of this plan is that it is everyone’s plan and is supported by all the labor unions (CGT, CFTC), the agricultural unions and the .employers’ union. The success of the model is largely based on the support of all the country’s economic players united behind a single goal: to rebuild France and relaunch its production capabilities. Jean Monnet again experiences, in a very different context, the power of concerted collective action and how people can forget their differences when they work together towards a common goal.

The Monnet plan has largely contributed to the reconstruction and modernization of France, to the resumption of growth and the reduction of unemployment during the post-war period. According to France Stratégie, the heir to the Commissariat au Plan, “the objectives of the first Plan, or Plan Monnet, have largely been achieved and the priority given to basic sectors has proved effective. (…) The Plan has instilled a new state of mind among business leaders, without undermining private initiative”[1] .

During these post-war years, Jean Monnet often traveled to the United States to promote the French plan for modernization and to solicit aid as the French economic situation remained extremely precarious. He realizes and worries about the extreme dependence in which France and Europe find themselves vis-à-vis the United States. The Truman administration, for its part, is worried about seeing the weakened European countries at the mercy of Soviet communism and begins to consider the rebirth of West Germany as a guarantee of future stability.

Monnet expresses again in 1948 his conviction that to face the perils and challenges with which the European countries were confronted, and which could give rise to fears of the imminence of a new conflict, the intergovernmental coordination mechanisms of the past are insufficient. The rebirth of a strong and potentially once again dominant Germany is a great concern to Monnet, as is the imbalance of power with the United States and the emergence of new blocs against which a disunited Europe will have little weight. He is convinced that the time has come for the countries of Europe to take their destiny into their own hands, to unite and together create the conditions for a lasting and prosperous peace. It is time to initiate this process of unificatio with decisive action Monnet first naturally approaches the very familiar Great Britain to which he proposes in 1949 a common, supranational management of Marshall aid. Faced with the refusal of the British, who were firmly anchored in the United States, proud of their Empire and jealous of their sovereignty, Monnet turns to Germany. He is aware of the need to find a solution to the question of the rapid revival of Germany, which is causing growing tensions in Europe. The Americans themselves, who largely finance European reconstruction and willingly recall that they have already intervened twice to settle world conflicts of Franco-German origin, are anxious to find a way to bring about a rapprochement between the two nations.

With this sense of the moment that is innate to him, Jean Monnet seizes this opportunity to propose to Robert Schuman the pooling of the coal and steel resources of the two former enemies, under the authority of an independent entity. This proposal, which will give birth to the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) is drafted by Jean Monnet with his collaborators during a long working session in his house in Houjarray in the Yvelines. Referring to the obstacles standing in the way of union, this historic note to Robert Schuman, dated 28 April 1950, explains: “The way to overcome them is to immediately take action on a limited but decisive point: the joint production of coal and steel would immediately ensure the establishment of common bases for economic development, the first stage of European federation (…)”. The Minister of Foreign Affairs immediately sees the historical significance of this proposal and agrees to promote it politically and to public opinion. On the German side, the offer is unexpected: it amounts to an instantaneous reintroduction of yesterday’s enemy into the camp of the “visitable” nations, albeit at the price of major concessions. Indeed, the plan gives access to France and the other future signatories of the treaty to important German resources. Nevertheless, Chancellor Adenauer also perceives the historical significance of the proposal and immediately accepts it.

On 9 May 1950, Robert Schuman makes a solemn declaration announcing the ECSC project and inviting all interested countries to lay with France and Germany “the first concrete bases of a European federation”. Italy and the Benelux countries join them to create the first European community. The 1951 Treaty of Paris ratifies the creation of the High Authority, the Assembly of Six, a Court of Justice which ensured compliance with the Treaty, and a Council of Ministers which ensures the harmonization of the policies of the Member States. The institutional foundations of the first European community are laid, and the Community method, also called the Monnet or Monnet-Schuman method, is born.

Jean Monnet becomes in August 1952 the first president of the High Authority of the ECSC based in Luxembourg. From 1953, coal and steel circulates freely in Europe for the greatest benefit of consumers and producers. To all, Monnet tirelessly repeats the essence of his method: “we are here to accomplish a common work, (…) not to negotiate advantages, but to seek our advantage in the common advantage”. Jean Monnet sees the ECSC as the beginning of the European unification he called for in the Algiers note of August 5, 1943. He is not mistaken, as indicated by a personal handwritten note dated August 5, 1953 in which he writes “My life only begins now, everything now has been trials, attempts, education”.

Jean Monnet and his team foresaw that the operating principle of the ECSC would in due course extend to other sectors, creating de facto solidarities gradually leading to a European federation. The question of the army is of course in their minds, but they did not anticipate that this sensitive question would arise so soon. The invasion of South Korea on June 25, 1950 accelerated things. It again fuels the fear of a Soviet invasion and poses more urgently the question of West Germany’s participation in European defence. France and the other countries of Europe are not yet ready to accept the rebirth of a German army and Jean Monnet proposes to René Pleven, head of the French government, to carry the project of setting up a European army within the framework of a European Defense Community (EDC).

The project is delicate, especially since it is progressing in parallel with that of the ECSC, whose ratification nothing must come to threaten. The EDC leads to debates and political rifts commensurate with the challenge of creating a European army so soon after the end of the war and in the midst of the Indochina war. Approved by four of the six countries of the Community, including Germany, the project is finally rejected by the French Parliament in 1954. Faced with this failure, which he attributs to the fact that the idea was premature, Monnet feels disappointed. He once again measures the difficulty inherent in the principle of “asking sovereignty to delegate sovereignty” outside of a crisis situation lending itself to extreme solutions. No doubt, minds were not yet ready for such an initiative, which the absence of a political community would have made in any case very difficult to implement.

As for Jean Monnet, the failure of the EDC signaled to him the need to devote himself entirely to the construction of the European edifice. He therefore resigns from his post at the High Authority, declaring to his collaborators: “What is in the process of succeeding for coal and steel in the six countries of our community must be pursued until its completion: the United-States of Europe (…). Our countries have become too small for today’s world, on the scale of modern technical means, of America and Russia today, of China and India tomorrow”.

Jean Monnet has experienced at the Plan and then at the ECSC the power of the approach consisting in relying on the organized forces of the nation to develop and then execute a common plan. It is the same idea that underlies the composition of the Action Committee for the United States of Europe. On the strength of his immense credit, Jean Monnet convinces in a few months the vast majority of the progressive parties and trade unions representing the six member countries to join the Committee and take part in its work. In France, only the Communists and the Gaullists do not join. What some will later call the “miracle” of the Committee is for Monnet a very simple formula: it is a question of creating the conditions for constructive debates between men who are separated by everything in their national political life by making them forget their oppositions and making them work on identifying common solutions to common problems.

To make the committee work, Monnet gathers around him a light team of loyal and efficient collaborators, in the front ranks of which François Fontaine, Max Kohnstamm, François Duchêne and Jacques van Helmont. The small team moves into an apartment on Avenue Foch lent by Silvia Monnet’s brother. The operating principle of the committee is to be mainly financed by its members, which guarantees its independence. Its statutes nevertheless allow it to accept external donations and legacies. Thus, for example, the Ford Foundation, which at that time financed numerous European initiatives in the field of research in the social and economic sciences (including, for example, the CERI, a body of the CNRS), also indirectly contributed to the work of the committee through grants paid to the documentation center of the committee established in Lausanne by Professor Rieben.

The first meeting of the action committee was held in January 1956. The issue they are tackling is that of Euratom, the objective of which is to unite European forces on the model of the ECSC to make up for Europe’s nuclear lag in relation to the major powers and facilitate its future energy independence. Convinced that the two treaties must be signed simultaneously, the action committee is committed to making progress on the Common Market in parallel. The two treaties, Euratom and the Common Market, are signed in Rome on March 25, 1957 and ratified by Germany on July 5. France ratifies the two treaties soon after. According to Monnet, the Franco-German reconciliation iss at that date “sealed in all its parts”.

At the end of 1957, domestic imperatives catch up with Jean Monnet :France is in a dire financial situation and the young head of government Félix Gaillard naturally turns to Jean Monnet, his former mentor, to help him apply for American aid. Jean Monnet’s mission to Washington is crowned with success. On his return, in March 1958, he expresses in a note to Félix Gaillard, a conviction that will later inspire the European Monetary System of 1972: “the objective would be the creation of a European financial and monetary market, with a European bank and reserve fund, the joint use of part of the national reserves, the convertibility of European currencies, the free movement of capital between the countries of the Community, and finally the establishment of ‘a common financial policy’. Like many ideas launched by Monnet’s action committee, it took a long time to find the right moment to turn it into concrete action .

The years 1957-1959 are years of relative convergence between Jean Monnet and General de Gaulle. The General supports the Common Market, Jean Monnet on his side supports the return to power of the General, votes in favor of the fifth Republic, and approves de Gaulle’s approach of the Algerian question. This rapprochement will not resist Monnet’s voluntarism on European issues. After the ratification of Euratom and the Common Market, Monnet’s action committee concentrates on three objectives: the enlargement of the Community to Great Britain, the development of new fields of action (such as agriculture), and the political construction of the Community, the principles of which are summed up in this simple formula: “delegation of sovereignty and joint exercise of this delegated sovereignty”. The foundations for a confrontation with General de Gaulle are laid. Indeed, de Gaulle openly calls for a European construction based on the inalienable sovereignty of States.

The Paris conference of 1961, chaired by the Gaullist Christian Fouchet, and devoted to the way of institutionalizing the political union of the six, does not succeed despite promising beginnings. In May 1962, De Gaulle makes a declaration in which he recalled his support for a Europe of nations States. In this declaration, he suggests that the model of integration supported by the Monnet committee is actually inspired by the United States, the true “federator of Europe”. and that it goes against the interests of European countries. Several ministers, including Pierre Pflimlin, resign to express their disagreement with General de Gaulle’s statements. Jean Monnet’s action committee at that time enjoys great prestige and strong influence due to the personalities Monnet associated with it and who truly considered the Committee as the instrument for the realization of their vision of the world and Europe. The views of the committee are strongly represented within the wide range of European parties and trade unions that make it up.

The committee therefore has to react against the Gaullist caricature of its action and in June 1962 it publishes a declaration which is intended to be educational and has a significant impact. In this decleration, Monnet explains the approach and method supported by the committee. “The method of Community action is a permanent dialogue between a European body responsible for proposing solutions to common problems and the national governments which express the national points of view (…). It is this method which is the real unifier of Europe. Apart from this difficult and perhaps slow but inevitable and sure journey, the committee considers that there is only adventure for our separated countries and the maintenance of the spirit of superiority and domination which yesterday almost led to the ‘Europe to its doom and could now drag the world into it’

Of course, Monnet appreciates that asking national powers to voluntarily share some of their sovereignty is an arduous task that will take time. But he is also convinced that the method is the right one and he is in no hurry.

The crisis provoked in June 1965 by General de Gaulle, known as the “empty chair” crisis to oppose the establishment of the common agricultural policy and majority voting at the Council of Ministers again put European construction to the test. Jean Monnet publicly announces his intention not to vote for General de Gaulle in the presidential elections of December 1965, which will see him support Jean Lecanuet in the first round and François Mitterrand in the second.

For Monnet, de Gaulle’s policy was fundamentally contradictory: it weakened Europe and by weakening Europe it weakened the very France he wanted to be strong.

Jean Monnet, anglophile since his adolescence spent in London, has always hoped and never doubted the ultimate rallying of the United Kingdom to the integration process once it had proven its effectiveness. Great Britain must, in his view, bring to Europe its world view, its science of government, its inventive capacities, and its resources. He has retained a strong link with the British administration and maintained a continuous and patient dialogue, which leaves the door open to membership at the appropriate time. The British, for their part, had rallied to the principle of a free trade zone but remained wary of the Community, of which they nevertheless witnessed the first successes. For Monnet, the temptation of an unregulated “wild” free trade is dangerous and can lead to a temptation of English domination in Europe. He conceives of the Community as a method of bringing people together, whereas free trade is only a commercial arrangement. In 1961, the British declare their readiness to apply for membership and negotiations begin, led by Edward Heath. As the discussions progress, de Gaulle openly and unilaterally takes a stand against the United Kingdom joining the Community. Jean Monnet, shocked by what he perceives as a cavalier attitude on the part of General de Gaulle writes for himself: “We have entered the time of patience”.

In the spring of 1967, Great Britain renews its candidacy for entry into the Common Market. Again, de Gaulle comes out against UK membership but the action committee formulates a resolution approved by the parliaments of the six which opens the way to negotiations. The departure of the leader of Free France and the arrival of Georges Pompidou in 1969 mark a resumption of the European dynamic. The accession of Willy Brandt to the German Chancellery is also a positive factor. The chancellor supports several important proposals of the action committee, including economic and monetary union, the European monetary fund, and the beginning of a political union.

Great Britain’s accession to the Community, signed in 1972 and finally enshrined by popular vote in 1975, was not an easy undertaking. The British themselves had long hesitated and often doubted. In his Memoirs, Jean Monnet recounts this anecdote which may seem premonitory today: “An English customs officer recognised me one day and asked me: ‘I would like to be sure of this sir: when we have joined your Europe, will we be able to leave it’? This question expressed for Monnet an atavistic British fear of engagement.

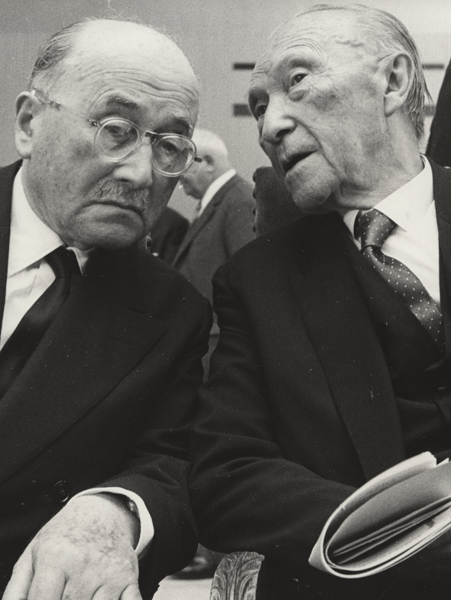

The dififculties encountered in France in the 1960s by Monnet’s action committee on the question of the accession of the United Kingdom and the construction of a political Europe provide Monnet with an opportunity to focus on relations between Euroipe and the United States. Jean Monnet thinks that these relations should be more structured and take the form of a partnership between distinct entities of equal power. Monnet continues to go often to Washington where he has many friends and he finds in the new Kennedy administration the stimulating and dynamic atmosphere of the Roosevelt administration. President Kennedy seduces him; he is young, simple, direct, intelligent and very positively inclined towards to the European project. Returning from one of his visits to Washington DC, Jean Monnet shares with Konrad Adenauer: “Everyone in the United States is now convinced that the organization of the West is necessary and urgent to solve the major problems of the world and that the European Community must be its backbone”. Two conditions however are expressed, which are consistent with the objectives of the action committee: that Europe organizes itself politically and that Great Britain joins it.

The assassination of President Kennedy, whose funerals Jean Monnet attends, has a significant impact on him. The young American president in whom he had placed a lot of hope had written him these warm words at the beginning of the year: “Under your inspiration, Europe has in less than twenty years progressed towards unity more than it had done for a thousand years. With Kennedy’s death vanishes Jean Monnet’s hope of creating before long the Europe-United States partnership that he so ardently desires.

The early 1970s were conducive to a revival of the European political union agenda. Leaders Pompidou and Brandt support European construction, and French public opinion is mostly in favor of the idea of a European government and the election of the European Parliament by universal suffrage. In October 1972, the European Conference endorses the proposals of Monnet’s action committee for an economic and monetary union and for the creation of a European monetary fund. These proposals however come up against the Council of Ministers of the member countries which reject them. For Monnet, they act by doing so not in the common interest of Europe but according to their national interests alone.

In 1974, Jean Monnet successfully supports the idea, strongly advocated by the new French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, of the formalization of a European Council of Heads of State deciding by majority and the principle of the election of European Parliament by universal suffrage. For him, a fundamental step has just been taken on the road to political union in Europe. No doubt Jean Monnet sees at this moment in Helmut Schmidt, the German Chancellor, and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, the French President, the men who will be able to continue his work, give new impetus to European construction and achieve his vision.

On May 9, 1975, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Schuman Declaration, the Action Committee for a United States of Europe is officially dissolved. Jean Monnet is 87 years old and he retires to his Houjarray house to write his Memoirs. François Fontaine assists him assiduously. There is no doubt that the book would never have seen the light of day without him. The purpose of the Memoirs is not for Monnet to recount the events of his life, which he is reluctant to share, nor to take a nostalgic look at the past. The aim of the book is to “attempt, as he writes, to enlighten those who will read (it) tomorrow on the profound need for European unification, the progress of which continues unabated through the difficulties”.

When one has accumulated a certain experience of action, he writes, it is still action to endeavor to transmit it to others, and the moment comes when the best one can do is to teach others what one believes to be right. There is one method to build Europe – there are not two in a given time. We have not left the time of the European Community, the time of the delegation of sovereignty to common institutions, the only means of ensuring the progress and independence of our peoples and the peace of this part of the world”.

In 1976, Jean Monnet received the title of Honorary Citizen of Europe, a title since awarded to Helmut Kohl and Jacques Delors. He dies on March 16, 1979 in Houjarray and his ashes are transferred to the Panthéon in 1988.

Gérard Bossuat, Andreas Wilkens, Jean Monnet, l’Europe et les chemins de la paix, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 1997.

Gérard Bossuat (dir.), Jean Monnet et l’économie, Bruxelles, Peter Lang, 2018.

François Duchêne, the First Statesman of Interdependence , New York, London, Norton, 1994.

Pascal Fontaine, Jean Monnet, l’Inspirateur, Paris, Grancher, 1988.

Jean Monnet, Memoirs, London, Third Millenium Publising, 2015.

Clifford P. Hackett, A Jean Monnet chronology 1888-1950 , Washington DC, Jean Monnet Council 2008.

Richard Mayne (compiled by Clifford Hackett), The Father of Europe. The life and times of Jean Monnet, Lausanne, Jean Monnet Foundation for Europe, 2019.

Eric Roussel, Jean Monnet , Paris, Fayard, 1996.

A l’écoute de Jean Monnet, Jean Monnet Foundation for Europe, Lausanne, 2004.

[1] https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/actualites/premier-plan-de-modernisation-dequipement#_ftn3